In early March, when the COVID-19 pandemic began shuttering businesses and schools across the United States, Chris Brooke wondered how he would teach his classes online. As the virus spread with astonishing speed, it became frighteningly clear that COVID-19 threatened something far greater than just the spring semester, and Brooke, a professor of microbiology, asked a bigger question: How can we help stop it?

At the same time, discussions were underway between Carle Health and the University of Illinois to develop plans to curb the pandemic. Brooke recruited colleagues to help, sparking a campuswide effort now underway to dramatically increase COVID-19 testing in the local community and the entire state of Illinois.

Spurred by reports that local health officials lack the means to process tests for the coronavirus, units across campus, including the Department of Chemistry, have mustered machines, materials, and personnel to partner with Carle Health in establishing a COVID-19 testing site.

Not only has the effort allowed healthcare workers at Carle to begin testing for COVID-19, thus reducing the wait period for local tests to within 24 hours in many cases, but the University of Illinois has now expanded the partnership to the Illinois Department of Public Health and Illinois Emergency Management Agency to ramp up testing operations. Laboratories across campus are mobilizing to provide COVID-19 testing supplies for thousands of tests across the state.

“It’s been a tremendous team effort, involving lots of people and lots of different partnerships. It’s one of the best things about U of I. We know how to work together. It’s so amazing to see everybody team up and try to get something done that’s impactful,” said Marty Burke, the May and Ving Lee Professor for Chemical Innovation in the Department of Chemistry and associate dean for research at the Carle Illinois College of Medicine. “This is just how we roll.”

Brooke, who specializes in human virology, spoke to local officials and learned that local healthcare providers were unable to perform adequate testing for COVID-19. Test samples were being sent away to state labs for analysis, leaving patients to wait for days before they knew the results.

The reasons for the complications in COVID-19 testing are many, Brooke said. The procedures necessary to test for the coronavirus are more involved and less user-friendly than those for other viruses, such as influenza. Nationwide restrictions on COVID-19 testing and supply shortages also contributed to the slow start in testing, he added.

Brooke said that it became clear that local medical centers had very limited capacity to run adequate numbers of molecular testing for COVID-19.

“The test is basically a procedure that we do in our lab on a daily basis,” Brooke said. “I didn’t really understand why, locally as well as around the country, we were struggling to perform this critical test that was based on this really common procedure that research labs around the country are doing regularly. So that’s what got me engaged.”

Responding to a request for help from Carle, Brooke approached research partners around campus for assistance providing Carle with the means to conduct tests, and the response was immediate. Following a flurry of assessment, legal work, and support from the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Innovation to clear regulatory hurdles, campus laboratory machines were loaned to Carle. Within days, the necessary components were in place to begin test validation, and COVID-19 testing was launched.

“While Carle had the ability and expertise to test within our lab, it’s not on the scale that would become necessary as this region reached the level of COVID-19 community spread,” said Kayla Banks, PhD, RN, and vice president of quality at Carle Health. “By partnering with the University of Illinois to use additional equipment, we’ve been able to increase testing capabilities for the region. We can now deliver results within 24 hours which means patients and physicians have answers sooner to determine appropriate care.”

Providing personnel and machines for local testing

Three campus units, the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology (IGB), the Roy J. Carver Biotechnology Center (CBC), and the College of Veterinary Medicine, have loaned equipment, supplies and personnel to support the work. IGB and CBC provided real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) instruments, which have the ability to amplify and identify specific RNA segments within a sample. If COVID-19, an RNA virus, is present in a mucus sample taken from the patient’s nose, the machine has the sensitivity to detect and confirm whether that patient has COVID-19.

Mark Mikel, CBC associate director, said that an engineer from ThermoFisher Scientific, which manufactured the center’s qPCR instrument, came to help enable the transfer to Carle and conduct re-calibration for optimal performance. Mark Band, director of the CBC’s Functional Genomics facility, assisted staff at Carle with installation and setup.

“The response on campus has been totally unselfish,” Mikel said. “If we find something in the lab that is needed for COVID-19 diagnosis by Carle, we give it to them. It’s been really a highly orchestrated effort across campus.”

Carol Maddox, professor of pathobiology and microbiology section head of the Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory in the College of Veterinary Medicine, said that the lab provided Carle with an RNA extraction instrument, used to purify the viral RNA for RT-PCR amplification to detect COVID-19. They also provided multi-channel and dispensing pipettors, used for transfer and precise measuring, to help staff increase the speed and ease of handling specimens and reagents. Thus, patients at Carle, OSF Health, and Christie Clinic have, in many cases, been receiving test results within a day.

As the veterinary laboratory routinely performs animal disease surveillance, Maddox said, two Veterinary Diagnostic Lab staff members, Therese Eggett and Evette Vlach, stepped forward to help train Carle employees to operate the instruments.

“They (Eggett and Vlach) have also passed the COVID-19 proficiency tests and are now assisting the Carle staff so that additional testing can be performed, including on weekends and evenings, increasing the capacity for COVID-19 testing,” Maddox said.

The donation of testing components for local and state testing

Two initiatives took shape on campus to provide COVID-19 testing supplies that are in drastically short supply: one was focused on the creation of nasopharyngeal swabs, and the other was focused on creating liquids necessary to conduct COVID-19 testing.

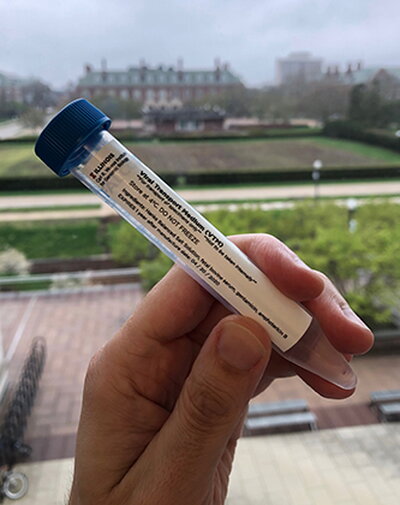

Brooke, Burke, and Doug Mitchell, Alumni Research Scholar Professor of Chemistry, collaborated to mass produce liquids necessary for COVID-19 testing, including buffered saline and viral transfer media (VTM), an essential mix of buffers, nutrients, and antimicrobials that’s in short supply. VTM is used to preserve test samples from patients until testing occurs.

As faculty with appointments in the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology, they were granted laboratory space in the institute to begin producing VTM using base materials from their own research supplies. A pair of laboratory technicians from Burke’s laboratory, Justin Lange and Akanksh Shetty, stepped forward to help, and soon the team was mass producing VTM. That caught the attention of state officials, who asked them to produce enough VTM for 10,000 tests per week. The VTM will be sent to a state laboratory in Springfield, with Illinois Emergency Management Agency reimbursing the university for the direct cost of the product.

As the agreement with the state of Illinois took shape, the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology made available six more laboratory spaces, in addition to the one already being used, to scale up VTM production. With additional faculty and staff stepping forward to assist with production, Burke said, the lab teams could be producing enough VTM for 20,000 COVID-19 tests per week.

“It has been deeply gratifying to see how faculty, staff, and students have stepped up to make it possible for the institute to contribute to this critical effort, from sourcing scarce materials, to facilitating deliveries, to organizing, training, and supervising staff, to actually preparing the VTM,” said Gene Robinson, Swanlund Chair of Entomology and director of the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology. “This has been an inspirational team effort fueled by altruism.”

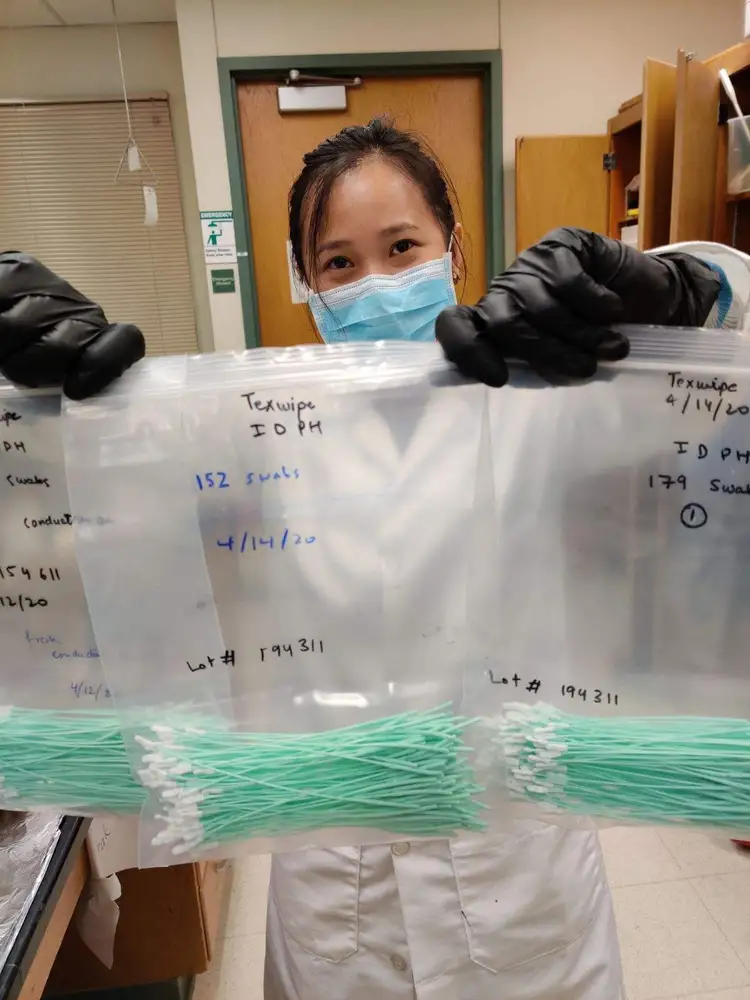

Meanwhile, another campus team is spearheading the mass production of nasopharyngeal swabs (also in short supply), which are used to collect test samples from patients’ noses. In collaboration with Carle diagnostic labs, the team reverse-engineered a commercial swab to design and test their own.

The team, which includes Mitchell, Jeffrey Moore, a Stanley O. Ikenberry Chair and professor of chemistry and materials science and engineering, and director of the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science & Technology, and Nancy Sottos, a Swanlund Chair and

head of the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, developed a method to create enough swabs that, if validated, could meet a portion of the need in the state of Illinois.

The team also includes Martin Gruebele, James R. Eiszner Endowed Chair in Chemistry and head of the Department of Chemistry, providing oversight as the plan calls for using glassware ovens found in organic chemistry labs in Roger Adams Lab to create the swabs. Mitchell described the process as converting a precursor rod into a viable swab using a hot draw. The key, he said, is to stretch the material in a way that retains rigidity in the handle while allowing for flexibility in the portion that enters the patient’s nose.

The Beckman Institute is creating a training video which can demonstrate how to create a swab within about 90 seconds. Once the swabs are validated at Carle and the Illinois Department of Public Health, group members and other researchers plan to produce up to 300,000 swabs to help deal with the crisis.

“We came to the lab to reverse engineer the nasopharyngeal swab with a safe, inexpensive, rapid, scalable method from common laboratory supplies and equipment,” Moore said. “When our initial idea hit a snag, the graduate students put their ingenuity to work and improvised a brilliant solution that checked all the boxes.”

Mitchell said it hasn’t been easy to essentially turn an academic environment into a factory to fight COVID-19, but he is strongly motivated.

“Healthcare workers are those on the front lines of dealing with this disease; however, there is essentially no testing being done on those individuals who are exposed every day to patients with COVID-19,” he said. “How many people have been infected in hospitals and in the community through asymptomatic transmission of the virus? Without widespread testing, we will never know. The amount of testing that has been done thus far is a very far cry from what needs to be performed.”

Brooke said that it’s been stressful to get the testing up and running, but that he feels some satisfaction for making a difference.

“What we’re doing is small,” he added, “compared to the health workers who are actually serving patients on the front lines.”

Read more about other COVID-19 projects by Department of Chemistry faculty members here.