A recent clinical study demonstrated with a high-degree of accuracy that positron emission tomography (PET) scans can be used to distinguish between breast cancer patients who are likely, and those who are unlikely, to benefit from hormone therapy.

The clinical trial utilized an imaging agent that attaches to progesterone receptors on cancer cells, making them identifiable in PET scans.

Nearly two decades ago, Professor John Katzenellenbogen, a research professor of chemistry at Illinois, began working on the design of the imaging agent, fluorofuranylnorprogesterone (FFNP), in collaboration with the late Michael Welch, a professor of radiology at Washington University in St. Louis.

When FFNP attaches to progesterone receptors on cancer cells, it can be detected with a PET scan.

“It took us about 10 years of work to get a compound that worked well in animals,” Katzenellenbogen said, while discussing the years of work to develop FFNP as well as other imaging agents.

His decades of research into the use of chemistry for improving cancer diagnosis and treatment has resulted in seminal work on the development of chemical and biophysical tools to study the estrogen receptor as well as the development of PET imaging agents which are used in the clinic to diagnose prostate and breast cancer.

In collaboration with Welch and other clinical researchers at Washington University, Katzenellenbogen has developed three PET radiopharmaceuticals that have gone on to extensive clinical studies: FES for estrogen receptor in breast cancer; FDHT for androgen receptor in prostate cancer; and most recently, FFNP, for progesterone receptor in breast cancer. FES was recently approved for general medical use by the FDA and is increasingly being used by many investigators throughout the world.

But it was during his work on FFNP that he suggested a protocol using FFNP in PET scans to measure progesterone receptor molecules as a way to identify whether or not estrogen receptors are active in breast cancer cells. The number of progesterone receptor molecules in breast cancer cells increase when active estrogen receptors are stimulated by their natural estrogenic hormone, estradiol, but there is no change in progesterone receptors if the estrogen receptors are inactive.

Doctors believe the reason that hormone therapy, an effective treatment for many estrogen receptor-positive breast cancers, does not work in half of all patients, is because estrogen receptors in cancer cells of those patients are not working properly.

Most breast cancers are estrogen receptor-positive, and hormone therapy is a common course of treatment even though there’s never been a really good way to identify which patients will benefit, especially as the cancer advances or recurs.

Now, researchers at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have tested that protocol in a small phase 2 clinical trial and “shown they can distinguish patients likely or unlikely to benefit from hormone therapy using an imaging test that measures the function of the estrogen receptors in their cancer cells,” according to a report by the university.

The five-year clinical study, which included collaboration with Katzenellenbogen, was done principally at Washington University in St. Louis by Dr. Farrokh Dehdashti and other colleagues, including Dr. Barry A. Siegel, a professor of radiology, and Dr. Cynthia Ma, a professor of medicine. The results were published in Nature Communications on Feb. 2, 2021.

Katzenellenbogen, who co-authored the article with Dehdashti, also worked extensively with the research team in preparing the grant that supported this work and served as a consultant on the research being supported by the grant after it was funded.

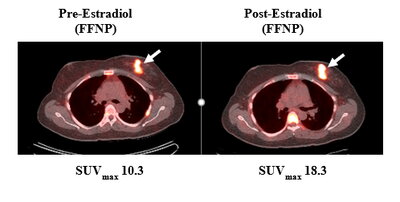

The clinical trial included 43 postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer who “underwent a PET scan using FFNP, followed by three doses of estrogen over a 24-hour period, and then a second PET scan a day after the estrogen treatment,” according a Washington University report on the study.

“For 28 women, the PET signal in the tumor increased considerably after exposure to estrogen, indicating that their estrogen receptors were working and had responded to the hormone by triggering an increase in progesterone receptor numbers. Fifteen women showed little to no change in progesterone receptor numbers after estrogen treatment,” according to the report.

Researchers continued monitoring the participants as they underwent hormone therapy, and “the disease of all 15 women whose tumors had not responded to estrogen worsened within six months,” and “of the 28 women whose tumors had responded, 13 remained stable and 15 improved,” the report said.

Katzenellenbogen said he is pleased with the results showing 100 percent agreement between the FFNP-PET response to estrogen challenge and the response to hormone therapy.

“In 43 patients, we could identify all responders and all non-responders, giving a prediction accuracy of 100 percent, which is very unusual,” he said. “With this study, we have established what appears to be a very promising protocol to accurately predict which advanced breast cancer patients will benefit from endocrine therapy. Also, we can make this determination within 1-2 days, whereas clinically it can often take months to decide who is responding and who is not.”

Even in advanced stages of breast cancer, Katzenellenbogen said some patients can still benefit from hormone therapies and avoid chemotherapy or radiation therapy. But, Katzenellenbogen explained, distinguishing between those who will respond and those who will not is challenging.

“This uncertainty can lead to unnecessary morbidity from overtreatment by chemotherapy for some who would respond well to endocrine therapies, and ineffective treatment and possibly disease progression when hormone therapies are tried for those who will not respond,” he said. “The bottom line of our work is that by doing two FFNP PET images to measure progesterone receptor levels before and one day after a challenge with estradiol, we can identify patients who will benefit from hormone therapies (the FFNP image in the PET scan becomes stronger) from those who will not benefit (their images do not change or become weaker).”

And the team observed 100 percent agreement between the response to estrogen challenge and the response to hormone therapy, even though the participants had advanced, often metastatic disease and had been through a variety of prior treatment regimens, Katzenellenbogen said.

The researchers conclude that this method should work for any treatment that depends on a functional estrogen receptor and could provide critical information to oncologists determining the best course of therapy for their patients.

The team is now moving forward with a larger, recently funded, phase 2 clinical trial with collaborators at other institutions who will attempt to verify the results.