After his first semester as a 16-year-old freshman at the University of Illinois, Richard Lazarus traveled to Europe for a while and returned to Urbana in the Spring knowing exactly what he wanted to do with his life.

“I picked environmental law during that time away. It was a good time for reflection,” said Lazarus, (BS, chemistry, ’76; BA, economics, ’76) an Urbana native and University High School graduate whose father was a physics professor at the U of I. “I was trying to find something I could care about and could be good at. I didn’t know any lawyers. I knew professors.”

He remembers flipping through the U of I course catalog, which was an actual book in the 1970s, to pick a major that was relevant to environmental law and offered a challenging course of study that would prepare him for admission to one of the top law schools in the nation.

An environmental chemistry course caught his attention, then an environmental economics course.

“I wanted to do something rigorous and hard,” Lazarus said. “The chemistry department was world class. One of the best chemistry departments in the country, and I was aware of that. My feeling was

that I was going to get a BS in chemistry, and I was going to take the hard path, and it was all to go to law school.”

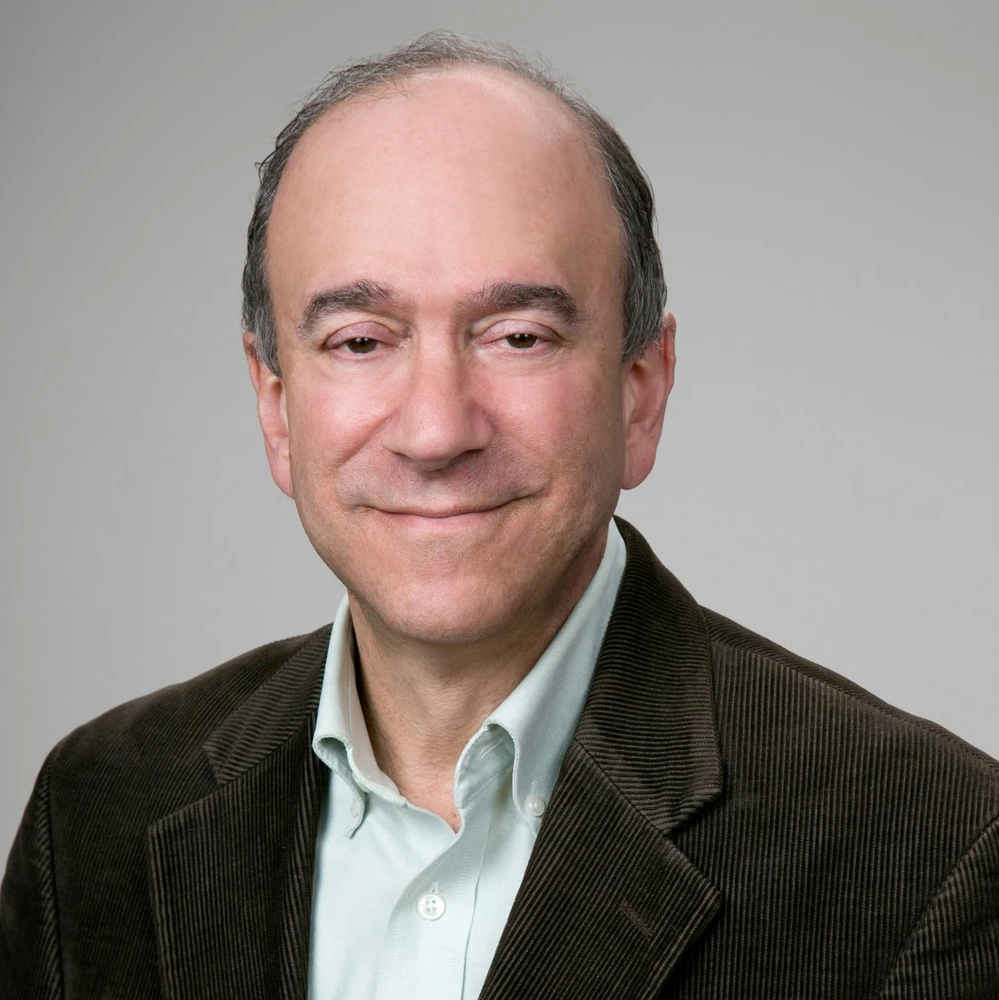

With dual degrees from Illinois in chemistry and economics, Lazarus went on to achieve his goal, graduating with honors in 1979 from Harvard Law School, where he is now the Charles Stebbins Fairchild Professor of Law. He teaches environmental law, natural resources law, Supreme Court advocacy and torts.

After law school, he landed his dream job in the U.S. Department of Justice’s Environment and Natural Resources Division. He worked hard and quickly impressed with his in-depth well-written and well-crafted briefs.

“I was so excited to be there,” he said. “I loved it. I worked all the time, and I enjoyed every second I was there … I was very driven.”

Now, a highly regarded environmental lawyer, professor, and author, Lazarus has represented the government and environmental groups in 40 U.S. Supreme Court cases and presented oral arguments in 14. He has written multiple environmental law books, and for 10 years, has co-taught a course on the history of the U.S. Supreme Court with Chief Justice John Roberts.

In 2010, he led the National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and was the primary author of the commission’s report to the President on the causes of the disaster, how to mitigate the impact and avoid such disasters in the future. Prior to Harvard, he was the Justice William J. Brennan, Jr., Professor of Law at Georgetown University, where he also founded the Supreme Court Institute, which prepares attorneys for oral argument in more than 90 percent of cases before the Supreme Court.

“It’s a complete thrill,” he said of arguing a case before the Supreme Court Justices. “It takes about 150 hours of prep for 30 minutes. Fifty to 75 questions in 30 minutes. You must give quick efficient and crisp answers. And, you do it under crushing pressure, but it’s also incredibly fun.”

As an undergraduate at Illinois, Lazarus said he was never under the illusion he would be a research chemist.

“My reach was going to be in a different skillset,” said Lazarus, who was basically crafting his own pre-environmental law program. “I wasn’t going to be a great research chemist. I was a terrific student, and part of it was dogged focus.”

With only one chemistry class in high school, Lazarus said he struggled in Chem 101, but he continually peppered the teaching assistant with questions, and by the mid-term, had the highest grade among hundreds of students.

“I’m no genius,” he said. “I just worked really hard, because I was focused on what I wanted to do.”

Lazarus went on to do well in all his chemistry courses at Illinois. Throughout his career, he has drawn on his chemical science knowledge and the analytical skills he learned doing experiments, not only in work associated with the science of climate change but also in major projects he has undertaken.

In talking about the science of pollution, Lazarus said he shares with his students his basic theory that you can’t understand the law unless you understand the underlying science.

“You must understand how the science works to craft laws,” said Lazarus, who explained how he has also used in his career the skills he developed in his Quantitative Analysis Lab course – CHEM 223.

Lazarus said it was the single most important class he ever took. He said you had to figure out how to complete in just three to four hours a 20-step experiment that would take 12 hours if done step by step. You had to decide, he explained, what could be done simultaneously, what could be done quickly with less precision, and what had to be done with ultimate precision.

“That was a really important class for me. And a hard class,” he said. “But that was such an important thing to learn. I use what I learned in that class in everything I do.”

Especially in 2010, he said, when he led a staff of 60 in the presidential investigation of the BP oil spill – an undertaking that easily could have taken three years but had to be done in six months, including writing the report and getting it on the President’s desk.

He employed the same approach, he said, when researching and writing his latest book, “The Rule of Five: Making Climate History at the Supreme Court,” which tells the origin story of Massachusetts v. EPA that resulted in the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in a 5-4 decision that greenhouse gases are air pollutants that can be regulated by the EPA.

It was as a student in the Environmental Chemistry course at Illinois when he first learned about global warming. The 1972 edition of Stanley Manahan’s textbook used in that class had an entire chapter devoted to the subject, Lazarus said.

“Chemists were all over [global warming] in the 1970s,” said Lazarus, who explained how he made an appointment before resuming his classes as a freshman with the professor who taught that environmental chemistry course, Professor David Natusch. Despite not performing well in his only high school chemistry class, Lazarus laid out for Natusch his plans to get degrees in chemistry and economics.

Lazarus said Natusch could have easily dismissed him.

“Instead he was very welcoming,” Lazarus said. Natusch took the time to write out on the chalkboard all the courses Lazarus would need to achieve his goal. Later, Lazarus became a research assistant for Natusch. Another faculty member, the late Elizabeth Rogers, whose son was a close friend of Lazarus, was also an important mentor. His senior year she hired him to be a Teaching Assistant for the Chem 101 Lab.

“Because they ran out of graduate students,” said Lazarus, who also mentioned the late Gilbert P. Haight Jr., an ACS award winner for his innovative teaching style and the author of multiple textbooks. He taught many of the introductory chemistry courses and enjoyed blending multimedia and television into his lectures and lab classes. He also mixed humor with explosive demonstrations in an annual lecture.

“A phenomenally fun teacher, who blew things up. Very entertaining as a teacher,” said Lazarus, who asked Haight during his senior year to be his faculty sponsor for an independent study class for him and a fellow senior. Haight gave the two seniors a lab next to his office.

“Basically, we tested all kinds of things,” Lazarus said, mentioning some explosions of their own making. “We would hear his voice say, ‘Careful.’ ”

At the end of the semester the senior duo had a show of their own – the chemistry of pollution – demonstrating all sorts of things related to air and water pollution in one of the lecture halls on campus.

At Illinois, Lazarus said he learned the value of rigor, education and discipline.

“I came away from my education there with that kind of confidence that I could figure things out when faced with a really hard unknown chemical compound to identify, and put my nose to the grindstone,” he said.

His advice to students is to figure out something you can do that makes a positive influence in the world whether in academia, government, or the private sector.

“Do a challenging thing in depth. I don’t care if you do it in chemistry or the tuba, but you’ve got to go beyond the surface and apply yourself to tough problems. For me, it was science,” Lazarus said.

Beyond law school, he never imagined he would argue cases before the nation’s highest court.

Most recently, he presented oral argument before the nation's highest court as the counsel of record for St. Croix County in Murr v. Wisconsin, which was decided in June 2017. Other major cases include U.S. v. Chem-Dyne, the first case to establish joint and several liability under the federal Superfund law, and a California Supreme Court case, National Audubon Society v. Superior Court of Alpine County, which applied the public trust doctrine to Mono Lake.

“I was good at figuring out good arguments...,” he said. “There was nothing pre-ordained or planned about it. It sort of came up in the serendipity of life, and I grabbed it.”

Prior to college, he said he always thought he would teach, and now that is a part of his career that makes him most proud.

“Inspiring and teaching and launching students. I’ve launched a lot of great students, so I’m very, very proud of my students. That part has been very fun,” he said. “I’ve got the best job in the world, and I get paid to do what I enjoy doing, and I get to do all of this other stuff on the side. Almost all of my [legal] work is pro bono now, and I can write what I want to write about.”