By Sharita Forrest, Research Editor, Illinois News Bureau

Around 1800, an English schoolmistress named Margaret Bryan wrote several well-regarded textbooks on astronomy and physics for young women. While Bryan corresponded with some of the most illustrious astronomers and mathematicians of her time, relatively little was known about her until now.

New research by Gregory Girolami, the William and Janet Lycan Professor of Chemistry at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, uncovered previously unknown details about this enigmatic scholar’s background and family. Girolami shared his findings in a paper published in Notes and Records: The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science.

The names of Bryan's daughters have been a mystery for 200 years. By combing through a relative’s will, Girolami was able to find their names at last – Ann Marian and Maria.

“Although Bryan’s published work and her efforts to educate young women have long been appreciated, now for the first time Bryan the person – along with her family – begins to emerge from the dark shadows in which she has been shrouded for over two centuries,” he wrote.

Girolami’s research sprang from his interest in the history of science – and women scientists in particular. His wife, Vera Mainz, also a chemist, shares his interest.

“When I started my investigation, Margaret Bryan was just this cipher,” he said. “It was known that she wrote these textbooks, she had two daughters and ran a boarding school, but that was about it. I like sleuthing challenges of this sort, so I decided I would try find out more about her life.”

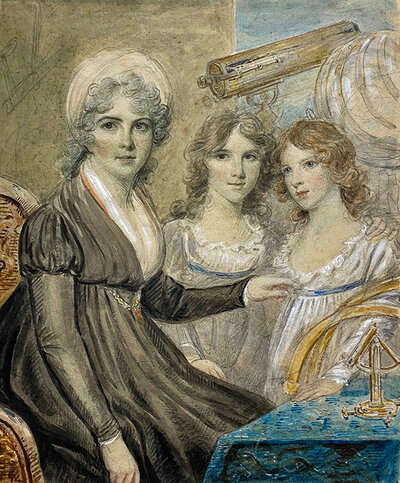

Basic facts about her seemed lost to history, such as her birth and death dates, maiden name and her family members’ names. Although the frontispiece of her first work, “A Compendious System of Astronomy,” a textbook for young girls, included an engraved portrait of the author and her daughters, the names of the latter were not disclosed.

Likewise, while the book’s preface implied that Bryan was a widow at the time of publication in 1797, the name of her husband has never been known, Girolami said.

Bryan’s other works included the physics textbook “Lectures on Natural Philosophy,” published in 1806; a smaller volume, “Astronomical and Geographical Class Book for Schools,” in 1815; and a revised edition of an educational board game, “Science in Sport or The Pleasures of Astronomy,” in 1804.

“Margaret Bryan’s astronomy book is very technical and comprehensive, and it includes some of the latest discoveries and understandings of astronomy as a science,” Girolami said. “Most women at that time did not get a good education. Those in wealthy families were well-educated in literature, languages, music and household arts, but it was not common for them to learn much about science.”

Noting that numerous people with the surname Nottidge – many of whom also were listed as residents of the village of Bocking – were among the subscribers to Bryan’s books, Girolami began his search there, hypothesizing that these individuals were likely relatives.

By combing through online genealogy databases and other sources, he found information about the Nottidges, a prosperous family of wool merchants who operated mills in several towns northeast of London.

Digging deeper, Girolami found that one of the family members, Thomas Nottidge, wrote a will in 1794 that not only mentioned Bryan, it revealed the names of her daughters – Ann Marian and Maria. Unfortunately, though, the will did not indicate how the families were related.

In investigating the family tree of Thomas Nottidge’s wife, Ann Wall, Girolami found that in 1768 her father, James Wall, left bequests to his three grandchildren – Oswald, James and Margaret Haverkam.

Girolami said he proved conclusively through his research that Haverkam was Bryan’s maiden name.

Although Bryan’s birth date could not be established, baptismal records indicated she was christened – likely as an infant but perhaps as late as age 2 – in October 1759, providing at least a general time frame when she had been born, Girolami said.

With further research, Girolami also discovered the name of Bryan’s husband – William Bryan, whom she married on July 12, 1783, in London. The births of Ann Marian and Maria followed, possibly in 1784 and 1786, respectively, Girolami said.

The date and place of Bryan’s death remain unknown, complicated both by her commonplace name and the vagueness of many public and church records. However, a notice of the death of “a much beloved and lamented, Mrs. Margaret Bryan, age 79,” on March 30, 1836, in Fortess Terrace, Kentish-Town, London, is a possible fit, Girolami said.

The timing of that death correlates with another source – the will of an attorney named Thomas Barnard Pinkett, to whom Bryan lovingly inscribed first editions of her two major books.

Although Pinkett’s will provided no clarity on the nature of his and Bryan’s relationship, Girolami said it established that Bryan and her older daughter, Ann Marian, were already deceased when Pinkett signed the will on Dec. 1, 1837, leaving “50 pounds sterling” to the surviving daughter, Maria.

With many questions about Bryan’s life and death unanswered, Girolami said he hopes his research will lead to even more discoveries about her – including how her interest in astronomy was piqued and nurtured to an extraordinary level during an era when women scientists were few.

Editor’s notes: To reach Greg Girolami, call 217-333-2729; email ggirolam@illinois.edu

The paper “Margaret Bryan: Newly discovered biographical information about the author of ‘A Compendious System of Astronomy’ (1797)” is available online or from the News Bureau.