Research from the University of Illinois and the University of California, Davis has chemists one step closer to recreating nature’s most efficient machinery for generating hydrogen gas. This new development may help clear the path for the hydrogen fuel industry to move into a larger role in the global push toward more environmentally friendly energy sources.

The researchers report their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

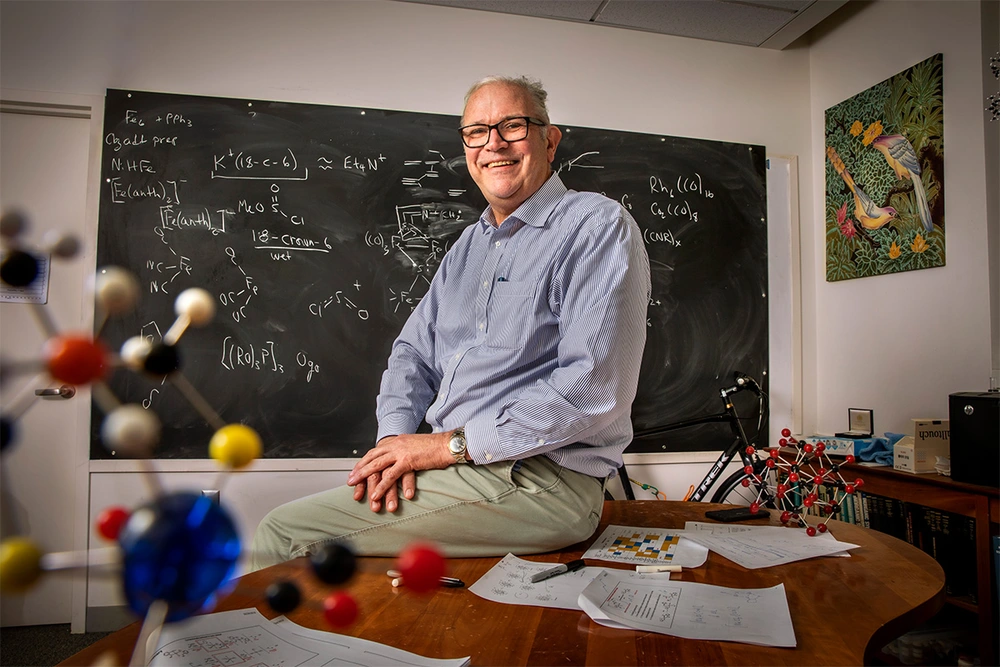

Currently, hydrogen gas is produced using a very complex industrial process that limits its attractiveness to the green fuel market, the researchers said. In response, scientists are looking toward biologically synthesized hydrogen, which is far more efficient than the current human-made process, said chemistry professor and study co-author Thomas Rauchfuss.

Biological enzymes, called hydrogenases, are nature’s machinery for making and burning hydrogen gas. These enzymes come in two varieties, iron-iron and nickel-iron – named for the elements responsible for driving the chemical reactions. The new study focuses on the iron-iron variety because it does the job faster, the researchers said.

The team came into the study with a general understanding of the chemical composition of the active sites within the enzyme. They hypothesized that the sites were assembled using 10 parts: four carbon monoxide molecules, two cyanide ions, two iron ions and two groups of a sulfur-containing amino acid called cysteine.

The team discovered that it was instead more likely that the enzyme’s engine was composed of two identical groups containing five chemicals: two carbon monoxide molecules, one cyanide ion, one iron ion and one cysteine group. The groups form one tightly bonded unit, and the two units combine to give the engine a total of 10 parts.

But the laboratory analysis of the lab-synthesized enzyme revealed a final surprise, Rauchfuss said. “Our recipe is incomplete. We now know that 11 bits are required to make the active site engine, not 10, and we are in the hunt for that one final bit.”

Team members say they are not sure what type of applications this new understanding of the iron-iron hydrogenase enzyme will lead to, but the research could provide an assembly kit that will be instructive to other catalyst design projects.

“The take-away from this study is that it is one thing to envision using the real enzyme to produce hydrogen gas, but it is far more powerful to understand its makeup well enough to able to reproduce it for use in the lab,” Rauchfuss said.

Researchers from the Oregon Health and Science University also contributed to this study.

The National Institutes of Health supported this study

Lois Yoksoulian | Physical Sciences Editor | Illinois News Bureau