By Meg Dickinson

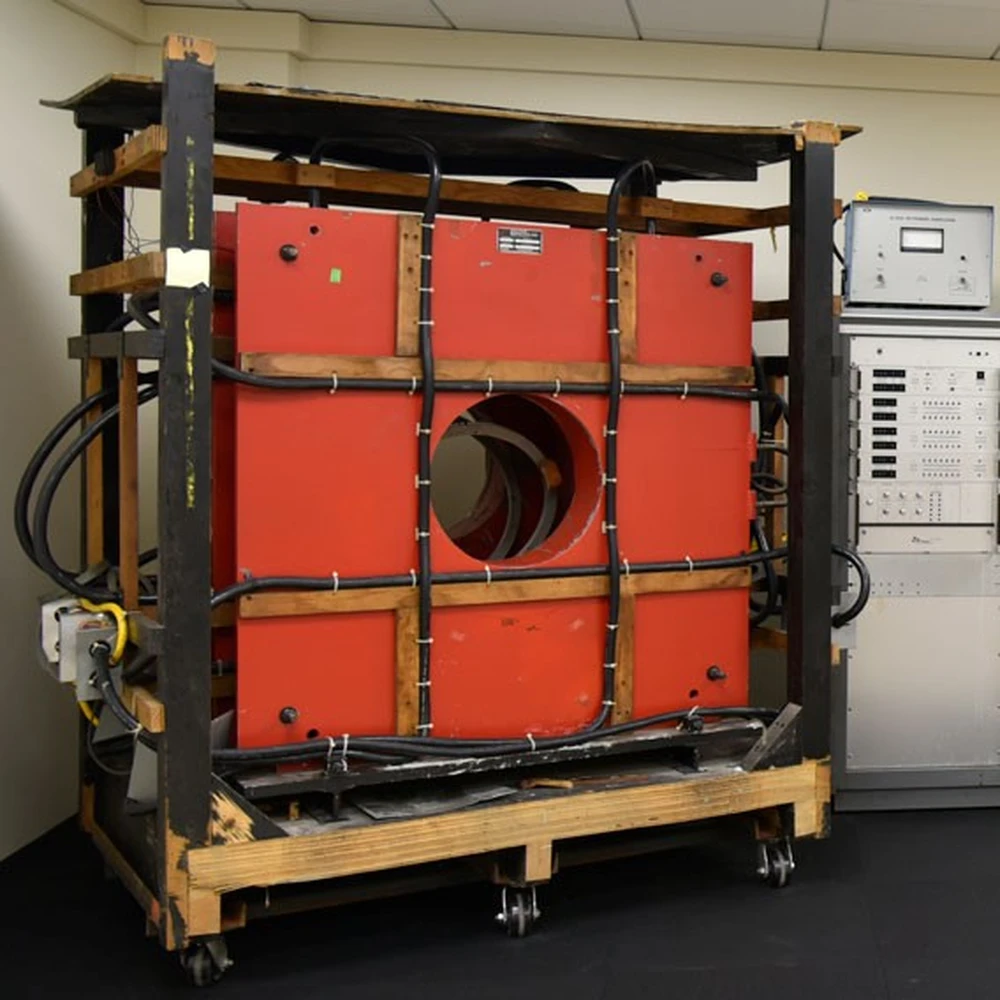

The first two human magnetic resonance imaging scanners, invented by late University of Illinois faculty member Paul Lauterbur, are now on display in the Illinois MRI Exhibit at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

The exhibit, which opened in the summer of 2020, celebrates the invention of MRI, as well as the foundational research that started on campus in the 1940s and 1950s that led to this world-changing innovation. The exhibit is accessed from the atrium of the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology.

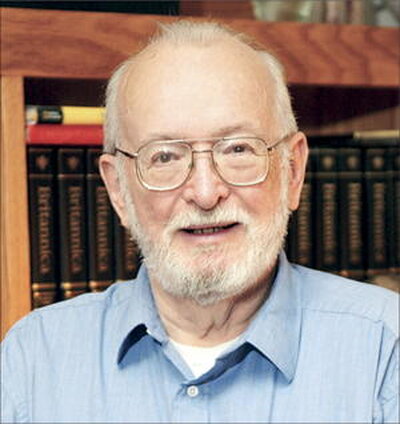

Lauterbur came up with the initial idea for MRI on Sept. 2, 1971, as a faculty member at Stony Brook University in New York. By Oct. 10 of the same year, his idea was working. In the 1980s, he was recruited to Illinois, where he was a professor of chemistry. In 2003, Lauterbur won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine along with British physicist Sir Peter Mansfield for their work in developing MRI. In 1962-1964, Mansfield had been a postdoctoral researcher with late physics Professor Charlie Slichter at Illinois.

Lauterbur’s original two human MRI scanners, which his lab had painted red, include all the components that still make MRI work today. Both are on display in the exhibit. Brad Sutton, a professor of bioengineering and technical director of Beckman’s Biomedical Imaging Center, discovered the scanners in a storage shed in Urbana in 2017.

“I received a call about a storage shed associated with Paul that I might be interested in looking through in case it had interesting artifacts,” Sutton said. “I didn’t know that we would find the data to Paul’s original experiments – thought lost to time – along with the first two human MRI systems. It is interesting to see his notes as he worked late nights for a month to go quickly from idea to images.”

With Earle Heffley, a member of Beckman’s facilities team and an MRI enthusiast, arrangements were made for the scanners to be transported to Beckman. A structural engineer with the university’s Facilities & Services assisted with plans to reinforce the floor to accommodate the two 3,500-pound magnets in the new exhibit space. The project involved opening the brick façade in Beckman’s atrium to open the former laboratory space to the public.

Beckman’s Communications Office, with help from University of Illinois librarians, dug into the rich history of nuclear magnetic resonance on campus to highlight the science, people, technology, and future of MRI at Illinois.

“Educating and inspiring students was important to Paul Lauterbur and his wife Joan Dawson,” Heffley said. “Paul and Joan helped found an independent kindergarten-through-eighth-grade school in Champaign. After Paul received the Nobel Prize, he gave a lecture on the invention of MRI to the entire school.”

Heffley, a member of the school’s board, called the new Nobel Laureate’s presentation to the students “as good as any I have heard delivered to any audience anywhere.”

Lauterbur also allowed the students to hold the prize medal.

“The students enjoyed hearing from Paul that his idea for MRI occurred while he was eating a hamburger in a fast food restaurant,” Heffley said.

Heffley called the Illinois MRI Exhibit “a labor of love” and believes it offers an extraordinary opportunity for education about the technology, especially because early products or prototypes don’t often survive.

Beginning in the late 1940s, notable faculty members like late chemistry Professor Herbert Gutowsky and physicist Slichter began working together on nuclear magnetic resonance, which was a precursor to MRI. Illinois has an incredible history of faculty members, graduate students, and postdoctoral researchers who discovered the phenomena that helped make MRI possible.

“Illinois faculty and alumni were involved in nearly every step in taking the technology from the early experiments of Slichter, Lauterbur, and others; to the commercialization that included Illinois alumni Walter Robb and Jack Welch,” Sutton said. “With such a rich history in the development of this pervasive life-saving technology, it is clear that this would not have been possible without the Illinois contributions.”

Although scientific research was male-dominated at the time, several women graduate students and researchers contributed to evolution of MRI at Illinois, including Geneva Belford. Between 1960-64, she programmed the ILLIAC I supercomputer to calculate the high resolution spectrum for the Gutowsky chemistry research group. She later went on to be a decorated professor of mathematics and computer science on the Illinois campus.

Much of the exhibit is shared on touchscreens through text, photos, infographics, and videos. A display case also shows a scanned copy of Lauterbur’s research notebook pages including the 1971 data that led to his MRI invention, as well as a replica of his Nobel Prize medal. Wall decals showcase his graphs, a high-resolution brain scan, and a quote from Slichter: “I had no personal competition with any of my colleagues. We were all there together.”

Jeff Moore, the director of the Beckman Institute, said this attitude of camaraderie and excitement across disciplines embodies the spirit of the Beckman Institute, even though it started decades before the institute was founded in the mid-1980s.

“The history shared in the Illinois MRI Exhibit is all about interdisciplinary collaboration,” he said. “It’s clear that these researchers were engaged in bold scientific risk-taking, and the resulting technology has changed the lives of patients. We know MRI has saved the lives of millions of patients and answered confounding health questions for many more.”

Today, Beckman is known for its MRI and biomedical imaging capabilities: It is home to two 3 Tesla human MRI scanners, a 9.4 Tesla preclinical animal scanner, and runs campus’ research at the Carle Illinois Advanced Imaging Center. The center is home to a new Siemens Healthineers MAGNETOM Terra 7 Tesla MRI, the only such scanner in the state and one of the first 10 of these systems in the country. The center is a partnership between campus and Carle Health.

Researchers from all over campus and beyond have used MRI technology at Beckman for decades to look at human behavior, brain function, understand blood and glymphatic flow, and even learn how different molecules are distributed throughout the brain. “Nuclear magnetic resonance and MRI are an incredible legacy on this campus,” Moore said. “The Beckman Institute is here to continue solving new problems and breaking barriers with this technology.”

Visit the exhibit: Find the Illinois MRI Exhibit in the first-floor atrium of the Beckman Institute, closest to the east entrance. It’s open to the public from 7:30 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. Monday through Friday. The institute is located at 405 N. Mathews Ave., Urbana.