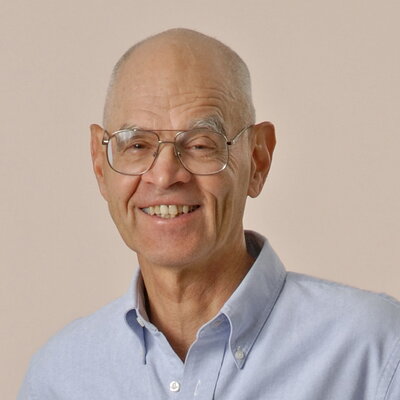

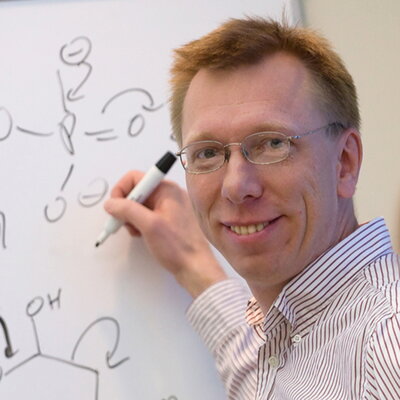

Peter Beak

UIUC Chemistry, 1961–2008

Here you will find a collection of memories of Peter from throughout the years.

Stories were submitted by current and previous faculty, and alumni.

Read the In Memoriam.

UIUC Faculty

“I remember Peter as a dear friend and a great colleague. I’ll always remember his joyous outlook on life. He was fond of saying, “You know, we are so lucky to have these faculty positions. Some days I feel that we ought to pay them to let us come in and do this.”

That buoyant attitude showed through in his interactions with his colleagues, the graduate students who were lucky enough to work under his direction, and the undergraduate students in his classrooms. He was a born teacher; there was a clarity in the way he talked about chemistry that shone through. Whether he was helping a student understand, or telling colleagues about new results from his lab, the stories were well told. Long after he’d acquired emeritus status, he was still teaching collaboratively with Jeff Moore or someone else. And he kept experimenting with new approaches to teaching.

He was exceptionally willing to give of his time and energy, whether in departmental affairs, in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, or at the campus level when he felt he could be of help. He was sought out frequently for committees that had to make difficult decisions. I remember his presence on the Campus Research Board during the time I was chair of that body. The work required tact, good judgment and a broad perspective, and he showed it in abundance.

Peter was a superb mentor for the graduate students and postdocs that spent time in his lab. To put it simply, they loved him. He was a real scholar; he showed genuine interest in the work of his colleagues, but at the same time, he was exceptionally modest about his own achievements.

Peter's joy in doing research was infectious. During the years when I was in administrative work and not much in the chemistry building, I nevertheless came by his office occasionally to learn what he was up to. I can just see him now, clearing off the chalk board in preparation for a crisp little lecture on the latest findings from the Beak group. It was fun to listen to him. He pretended I still recalled a lot of lithium chemistry, though it had been several years since I had actually worked in that field.

We became close friends over the years; when we were both emeritus faculty we still kept in touch and spent time together in Florida where I lived when he and Sandy came for vacations. I will miss my friend Peter Beak.”

“Peter Beak was an exceptionally thoughtful and highly impactful scientist, a treasured colleague, and an empowering mentor. His seminal work on chiral organolithium reagents made it possible for many of today’s chiral drugs to be practically manufactured on scale. He was the philosophical center of gravity for our Department that inspired us to always remember that our students come first. He enabled me in so many ways during the launch of my independent career, and he did it on purpose.

I had heard so much from Eric Jacobsen about how special Peter was, long before I first visited UIUC and met him in 2005. Perhaps it was because Eric’s characterization was so on point, or perhaps it was just part of Peter’s magic, but the first time I met him I felt like I was talking to a lifelong advisor and the conversation had picked up right where we left off last time. I was so grateful and excited to have the opportunity to begin my independent career in the Department he did so much to help build, and to occupy the office next door to his.

I will always remember how thoughtfully and generously Peter shared his guidance over the past 16 years, on everything from physical organic chemistry, “I would be delighted to speak with your group about thermodynamic/kinetic control with respect to prior diastereomeric equilibria. Is Tues Dec 1 a possibility?”… “It may be more useful to think of reactions first in terms of the limiting cases and then in terms of an intermediate case in which the rate of equilibration and ring closure can be competitive,“ to the education of undergraduates, “I am thinking about changes in 236 for next fall. I would appreciate your perspective on weaknesses you saw in students who came to 436 last spring from 236. I would like to try to make improvements that would fix any problems“, to the professional development of graduate students and post-docs: “I am going to meet with Suk Joong tomorrow [Monday] afternoon for a mock interview, I believe at 2:30. I would be happy to have you sit in if you think that would be helpful for any further coaching“ (remarkably, Suk Joong Lee was my first post-doc who, with Peter’s incredibly generous nudge, transitioned from Peter’s lab into mine soon after I arrived at Illinois, and Peter insisted on continuing to pay his salary from his own discretionary funds), to broadening the organic chemistry tent “I learned for Don DeCoste that you are planning a lab experience for rural high school students in January. I do not want to interfere but I would be happy to help if that would be useful”…”In my talk with the students on Thursday about reaction mechanisms I plan to show the reaction of salicylic acid with acetyl chloride to make aspirin and of aspirin with an amino group of a protein to explain its action. Does that fit in OK? Or would you suggest changes? I also plan to use an overhead and have them draw a few arrows and the structure of Aspirin“, to navigating the interpersonal challenges that will inevitably arise in a high-powered Department: “Could I see you for some advice for a few minutes Saturday sometime after 11am?”.

On countless occasions he sat down with me and/or my students, usually in my office or in the small circular table in his and spent anywhere from three minutes to three hours as needed sharing his wisdom. I learned and grew every time I spoke with him.

My favorite memory is from a dinner. Soon after Christina and I moved to Illinois, Peter and Sandy invited us over for dinner at their house. I remember the joy with which he shared stories about his grandchildren, stories about Roger Adams and many other colorful characters from our Department, and a particularly inspiring chat during a long cool swim together in the lake behind his house in the light of a brilliant sunset in Urbana. Persistence is as important as brilliance he told me. He also shared, with one of his signature laughs, that cornfields are great for long runs, because they serve as clear mile markers, and they go on forever.”

An Homage to Peter Beak

Composed on the Occasion of his Retirement 2008

There once was a chemist named Beak

Whose fame in the world reached a peak

For his well-known creation

Of 2-lithiation

By forces believed to be weak

My colleague obsessed with sec-BuLi

And reactions performed ultra coolly

Made anions with verve

That we all could observe

Though many behaved quite unruly

The test “endocyclic restriction”

Has undone a well-known contradiction

A special perversion

For retention/inversion

Led Pete to reveal his affliction

(+)-Sparteine’s a ligand so fine

And to Pete’s way of thinking divine

Is a pinch in each flask

Really too much to ask

Of every co-worker of mine?

“As a mentor and a friend, Peter was the colleague who had the greatest and most enduring influence on my career at Illinois. I first met him when I interviewed here, as a 24-year-old neophyte academic aspirant years ago. As typical, I was paraded from faculty office to faculty office, details of which I no longer remember save for my visit with Peter. He said two things about the department that impressed me deeply and convinced me to come here: First, although research is challenging, the department helps a lot by providing professionally staffed and subsidized service facilities, and generous TA and fellowship support. The second more important point was that this was an “open department”, with free access for all students to all of the faculty. “Faculty doors are normally open; so, you can just go in to speak with them, even if they are not your advisor.” Both of these proved to be true and continue to today.

Early on, I would frequently touch base with Peter when things troubled me about the times (the tempestuous early 1970’s) or worried me about the department, and his simple, principled analysis and unwavering encouragement were always helpful and uplifting. Most importantly, he applauded my deep dive into biological problems at a time when this was almost considered apostasy by most chemistry departments, and he assured me that my research would be evaluated fairly. In fact, throughout my whole career, whenever I needed to make a difficult decision or was seeking to be recharged, I would visit Peter’s office. There, I would not get a “pep talk”, but rather I was favored with a genuine discourse that was always encouraging and left me enlivened. Early on, for both Benita and me, Sandy and Pete’s kindness in inviting us into their home made us feel most welcomed into the University and the community. Peter’s passing is the loss of a great chemist, a great colleague, and a true friend. I—and many others—will miss him greatly.”

“I was fortunate to have an advanced undergraduate organic chemistry course from Peter (ca. 1983). He emphasized a conceptual way of thinking about organic chemistry that ingrained in me the habit of "reason-by-analogy". For example, when we discussed a complex, multistep synthesis, he asked the class to consider what this work brought to the field. "How did this synthesis transform the way we think about chemistry?", was the question he put before us. I'll forever carry that teaching with me.

When I joined Illinois' chemistry department in 1993, Peter was more than a colleague. He taught me to stay true to the mission of teaching and training students as our primary purpose. He instilled in me that our role as faculty is to put the well-being of students first and foremost.

He was also a critical reader of my manuscripts and the most significant Moore Group publications benefited from his chemical insights. When I became the director of the Beckman Institute, I brought on (then Emeritus) Prof. Beak to serve as the senior advisor to the director. He continued to offer support and sage advice until the very end. I will miss him greatly.”

“Well I have many stories about Peter Beak. It took me a while to get to know him because it was necessary to first convince him that I was not some egomaniacal jerk, which seemed to be his initial suspicion when dealing with faculty (and he was often correct). When I arrived at UIUC, pre-Internet, he was one of the faculty in the Chem Library on Saturday mornings, quietly checking through a stack of journals. He kept a log. Peter was loyal to his organic heritage, and one sensed that he felt strongly that he was part of a grand tradition of organic chemistry in RAL.

But the main thing about Peter Beak was his strong sense of decency toward students and colleagues. He was adamant that each student and each colleague carry their load by putting in good hours, being straightforward, and not grasping for attention. He was obviously amused, perplexed, and, sometimes, annoyed by the complicated interactions of personalities and their chemistry. In prelims and in meetings, he was slightly quiet but often playful. I can still hear his slightly croaking laughter that followed his explanation of a surprising insight.

While it was obvious that he greatly enjoyed his students and colleagues, he was especially beaming in the presence of his wife Sandy.”

“When I arrived at Illinois in 1997, my new rooms were next to the Beak laboratories. I could not have asked for a better location as Peter and his students made my fledgling research group feel welcome and helped us tremendously in setting up our labs. Peter invited us to his group meetings and for three years we continued this set-up. It provided my junior members with senior students to talk to, and it provided me with a close-up view of whom I considered the best mentor in our department. David Gin and I used to marvel how Peter time-and-again would turn his students into some of the strongest scientists in the program, regardless of the level that they came in at. He gave me one of the best pieces of advice when he said that a mentor should spend much time to find the right project for each student’s talents. His students truly loved him, and I could see why. He will be greatly missed but his influence on our program will be lasting.”

“Peter Beak was the first person I met at UIUC and he served as an informal mentor to me for my formative years in the Department. He was a highly insightful scientist who was always looking for ways to make positive contributions on the careers of younger scientists. At the time I arrived at UIUC, I had already published several independent papers describing an allylic C—H carboxylation reaction. I recall presenting this work to Peter in my office one afternoon and his response: “Have you considered using nitrogen nucleophiles, I think it would be very impacting”. He of course was right, and this gentle challenge inspired me to take that part of my program to the next level. This story in some ways exemplifies a gift Peter had in his mentorship which was to critique in a deliberatively positive and forward looking way that left you feeling energized and excited about the future.

Peter and his wife Sandy were the first adult guests that my husband Marty and I hosted at our house for dinner. We had no idea what we were doing at the time but the Beaks were extremely gracious. Peter was always stressing to both of us the importance of work/life balance for maintaining a long, productive and happy career. A few years back we had the opportunity to have the Beaks over again for dinner and I think Peter was impressed with how far we had come with respect to this. My last memory of Peter is him sitting on the floor of our living room playing with our two sons and looking extremely happy.”

“Peter Beak was my colleague, friend, and mentor for more than 35 years. It is fair to say that during this time he was my closest colleague, biggest supporter, and in many ways a second father. Writing this tribute raised several important questions in my mind. Most importantly, why did Peter take me under his wing at all? We are such different people. Early in my career I carried some New York pretensions, favoring designer clothes and four-star hotels, whereas Peter was much more down to earth. His preferred uniform was what his daughter Stacey referred to as his signature blue Oxford button down and khakis. Not to say he didn’t enjoy the finer things in life, for as I learned on an evening stop in Hayes, Kansas, on our way to a Colorado ski trip, Peter carried a VIP card to the Super 8 motel.

What I know for sure is that I am the beneficiary of our time together. Especially early in my career when I was very unsure of myself, Peter’s unwavering support meant the world. He was always honest and straightforward in offering advice and criticism and did so in just the most encouraging way.

Peter often said that being a Professor is the most privileged job in society. As a professor, he was the total package. He really knew how to approach scientific problems and critically evaluate research, going right to the core of any problem. His research accomplishments are legendary, but there is no question that Peter’s biggest impact on all of us was through his teaching and mentorship. He was a gifted and committed teacher. What faculty member would invest the time to take the top ten undergraduates on each organic chemistry hour exam out for coffee!? He was an amazingly patient teacher, encouraging and counseling me for about 20 years before I finally learned to mentor students the way that he did. Peter was an extraordinary advocate for students, creating and sustaining the Allerton Conference, serving as Director of Graduate Studies, and generally always putting the welfare of students above all else, including himself.

Perhaps the most important lesson that Peter taught me, and one that he conveyed both explicitly and through his actions was about work-life balance. Peter understood the difference between eulogy virtues and resume virtues long before they became the focus of contemporary books and essays. The tributes here, many that will barely mention his many scientific accomplishments, will show that, as usual, he was ahead of his time. He often told me that later in my life, I would never wish to have published one more paper, but I would regret not spending time with family. What an amazing gift to have a highly accomplished and respected senior colleague tell you that long before it was broadly an acceptable approach to academic life. And he lived by his words. Chemistry and teaching were his passions, but more than anything else, he loved his family. Indeed, he taught us all about loyalty and commitment having been married to his wonderful Sandy for 61 years. Peter was also a committed father and frequently shared his immense pride in Bryan and Stacey and their children.

So why did Peter give me so much in advice and friendship over these many years? I do not have an answer. Maybe it was a shared interest in diversity, social justice, and treating people with respect and dignity no matter their station in life. Or maybe it arose from our shared love of laughing and a self-deprecating sense of humor. We did enjoy ribbing each other. On a July trip to the Gordon Conference in New Hampshire, when Peter learned that I had only packed t-shirts he laughed with disbelief: “You think because it is ninety degrees in Urbana that everywhere in the world must be ninety?!” And he could just as easily laugh at himself. When my daughters were young, they would visit “Uncle Pete” in Roger Adams Lab on Saturday and draw a caricature of him on his chalkboard, a single line coming up from his head. He would rub the top of his head and roar with faux disbelief. “That is all the hair you think I have!?” Then they would all squeal together in laughter.

I will miss Peter’s laugh the most but take solace in knowing that he made the world a far better place. Peter Beak’s legacy is in making all of us better people.”

Former UIUC Faculty

“Peter Beak was my mentor, friend, and role model. I was on the chemistry faculty at the University of Illinois from 1988 to 1993, but I first met Peter when he did a sabbatical at Berkeley in the mid-1980’s. He attended a group meeting I gave as a third-year graduate student and met with me afterwards with follow-up questions and suggestions. I recall being deeply struck by his deep thinking, gentle manner, and extraordinary kindness. When I interviewed for a faculty position at UIUC a few years later, he not only remembered me, but he welcomed me almost as an old friend. We had a wonderful scientific discussion, and I still remember thinking how extraordinary it must be to have him as a colleague. Needless to say, I was thrilled when I did receive an offer.

Peter helped me in countless ways in my first years as a professor. Just weeks after I arrived, a talented 3rd-year graduate student named Wei Zhang sought to switch to the Beak group from the inorganic division, but Peter advised him to talk to me instead. I was deeply impressed by Wei in our meeting, but disappointed to learn that he was (quite understandably!) interested in working with Peter. I thanked him for talking with me and said goodbye. A few minutes later my phone rings, and it’s Peter telling me “Don’t be stupid! Grab that guy!!” I did, thankfully, and Wei played the key role in getting my program off the ground. That kind of generosity is extraordinary, and it was characteristic of Peter’s general attitude toward his junior colleagues.

As I started to grow my group, Peter invited me to hold joint group meetings with his. I learned so much watching Peter interact with his students. I remember him furiously taking notes during their presentations in his utterly illegible handwriting. Afterwards, he would sit down with the student who presented and give them detailed feedback. Every comment was insightful and constructive, and nothing was sugar-coated. His genuine concern for the education and development of his students is widely known and appreciated, but I got to see it very close up. It affected me profoundly.

Peter had highly sensitive emotional antennae, and an amazing ability to say the right thing at the most difficult times. At various moments of crisis in my life – from running injuries to rejected papers and grant proposals to family setbacks – he reached out and always left me feeling grateful for what I had and hopeful for what laid ahead. One of his lessons that left an especially deep impression on me was to recognize how incredibly privileged we are to work in a university. He saw the good in every student and coworker, and I think he appreciated sincerely the opportunity to work with them. But he was also street-smart and tough-as-nails. I especially admired his ability to identify and selectively ignore anyone with exaggerated self-importance (including letting me know when he thought I might be getting a little full of myself!).

As dedicated and professional as Peter was (and he may have been the most professional person I have known), I think he never took himself entirely seriously. For this I know we owe his wife Sandy a significant debt. The first time I met her, shortly after I was hired at UIUC, Sandy asked me “Do you work a lot of hours, like Peter?” Of course, I answered, ‘Yes!’, to which she added with feigned disgust ‘Well, I guess you’re not very smart either.’ I still remember Peter’s expression – one I saw many times – of both appreciation and resignation to Sandy’s skill in keeping him rooted squarely on the ground.

For reasons I will never fully understand but will forever appreciate, Peter and Sandy befriended me, and we have remained close for the past 30+ years. I have many personal stories and I doubt I can convey why they are so precious to me. Just one example: When Peter was elected to the American Academy of Arts & Sciences (a pretty big deal!), he and Sandy came to Cambridge for the ceremony, which was being held just a few blocks from where my office and labs are now located. We had a nice celebratory lunch together beforehand, accompanied by my wife Virginia and three children who were under 10 at the time. As we were finishing the meal and the kids were getting a little unruly, Sandy said ‘Okay Peter, we got to see Eric and Virginia, do we really have to stay for the rest of this?’ She was joking, of course, but it seemed they might really be thinking about bagging the ceremony.

I was especially fortunate, but many, many others were touched by Peter on both professional and personal levels. On this very sad occasion, I am reminded of David Gin, whose affection and admiration for Peter rivaled my own. In fact, David and I would occasionally get into something of a sibling rivalry arguing over which one of us had benefitted more from Peter’s mentorship.

I suspect others will comment on Peter’s extraordinary contributions to chemistry, so I will only share a personal perspective. My sense is that there is great excitement currently in the field of mechanistic chemistry, and it is now common to see some attempt at rigorous mechanistic characterization in papers focused primarily on methods development. That was far from the case during the first part of Peter’s independent career, a period during which “physical-organic chemistry” became an almost-dirty phrase synonymous to many with arcane research and irrelevance. I hold that Peter, perhaps more than anyone, was responsible for the renaissance in the field of physical-organic chemistry we are witnessing today. Rather than analyzing simple problems in extreme detail (which was the direction much of the field had taken in the 1960s and 70s), Peter focused on complex problems where deep mechanistic insight could be connected to applications of genuine value to synthesis. His work on carbanions and particularly on stereoselective lithiation chemistry is especially celebrated in that regard, but I see each of his papers as a masterwork in connecting a fundamental mechanistic question to a valuable reactivity concept. That approach has had a transformative effect on the field of reaction development, and it certainly shaped my own program.

I am grateful to the Department of Chemistry at Illinois for allowing me to share these remembrances of Peter. He meant the world to me.”

“Professor Peter Beak was a scientist whose work is acclaimed throughout the world and a teacher who inspired generations of students to pursue their dreams. But to me, above all of that, Pete was a mentor and a friend who was an indispensable part of my life for more than 45 years.

I met Pete for the first time in December 1974. I was a postdoctoral student on the market for an academic job interviewing at the University of Illinois, one of the top chemistry departments in the nation. Bill Pirkle, who like me was a PhD graduate of the University of Rochester, was the host for my visit and he arranged a dinner along with several other faculty members the evening of my arrival. It was a pleasant dinner, as such dinners go.

The next day, I gave the usual research seminar and met with faculty to discuss chemistry. Pete was among that group and he told me that the two of us would go to dinner that evening. Pete picked me up at the hotel and I was surprised to discover that we were going to the same restaurant I had been to the previous evening. I said nothing about that, at first. As the evening proceeded, we began by talking about chemistry, but the conversation quickly broadened, and we discovered several mutual interests. Eventually, I felt confident enough to mention that I had been to the restaurant the previous evening. Pete, grinned and told me that was because it was the only restaurant in Champaign-Urbana where you didn’t order at the counter. A friendship was born.

Anita and I, a three-year-old and a month-old infant arrived in Champaign the next July not knowing anyone and in desperate need of advice. I moved into my office in Roger Adams Lab and within a few days, Pete stopped by to offer assistance, which was gratefully accepted. Those first months were a blur of setting up a lab, recruiting graduate students, teaching my first course (to over 800 organic chemistry students) and getting settled into the rhythm of life in the department. Pete was there, volunteering to help whenever he could.

The friendship that began that December evening lasted until Pete’s death. I will miss him greatly. I will remember the ski trips our families took together. I will remember the time in a ski lodge cafeteria in Utah when a man came up to us and asked, Pete, “Are you Professor Beak”? He then proceeded to explain that he was a surgeon who as a student in Pete’s class had become motivated by his enthusiasm and obvious love of science and discovery.

I will remember when Pete and I were at an ACS meeting and he stopped by my hotel room asking to borrow a pair of pants because he had mistakenly packed only Sandy’s. But above all, I will remember a real gentleman who loved his family, who was dedicated to science and who selflessly gave to his students, colleagues and friends all that he possibly could.”

Alumni

“I have lost an extraordinary colleague and a trusted, giving friend. There has never been a moment where I doubted Peter was on my side. The counsel he offered was clear, based on the best available information and always, always, intended to be helpful. Without exception, I felt just a little better about life after spending time with Peter.

I knew Peter only by sight while a graduate student at Illinois, although he was a surprise last minute substitute on my thesis defense committee! He once found me cutting a rusty old frozen lock from my bike outside RAL. In his best deadpan voice, Peter suggested I take up the inadequacy of my skimpy graduate stipend with Chairman Gutowsky rather than begin a life of crime. We laughed about that...later.

I knew Peter as a great educator, not at the university but at Monsanto where he was a consultant for nearly all my 25-year career there. I think it fair to say consultants were not uniformly welcomed. Not so with Peter. His time was always filled to capacity because everyone knew their project would be on a better footing after being pressure tested by Peter. Those who met with him could go forward knowing the fundamental underpinnings of their project were sound or what needed shoring-up before proceeding or when to call an end to the endeavor. They too knew Peter was about their success.

Peter and I have been the beneficiaries of great spouses. Peter would often bring Sandy on his consulting visits. Having shared the dubious pleasure of life with a scientist, my wife Kay and Sandy became fast friends. The meals we enjoyed and the laughter, usually at the expense of Peter or I, made for an ever-deepening regard among the four of us. His kind invitation for Kay and I to participate in the annual Beak-Pines Conference ensured we remain connected.

My heart is broken but my gratitude for his company is beyond measure and the memory of my dear friend sustains and enriches me.”

“‘Please look over the section on…it is important that we are clear and accurate.’ This is the last line from a letter Peter sent me as we were wrapping up the planned submission of a manuscript based on some work I and a colleague had carried out as graduate students in his lab. Clear and accurate - apt words to describe his approach to science and much else. His ability to construct and deconstruct mechanistic arguments was remarkable. As a scientist he sought to understand with uncluttered clarity the reactions that he studied, several of which were developed in his lab. A regular user of Occam’s razor, he shared that skill with his students, showing us all how to keep it sharp and wield that blade properly, but also gently, with humility. Follow the trail of evidence and gather more where it ends - he modeled this in every single conversation, group-meeting, and scientific interaction.

The warmth of his personality, always shared with his broad smile and gregarious laughter, extended to his mentorship style - he saw and elicited the best in those around him, and was unfailing in redirecting the spotlight of credit away from him and toward his students for their ideas and successes. He once wrote that "my own interest in research is driven by the enjoyment of learning along with the students.” He led by letting us lead. Peter gave his students tremendous independence, which gave us the confidence to explore, to fail, and to learn. In turn, this enabled us to live up to the trust he had in us, which came with the expectation that if we persisted in forging our path, we would find it. He was clear about this, and although it may not have always been apparent to us at the time, it turns out he was accurate.”

“In 1993, University of Minnesota chemistry lost Paul Gassman, who left a bequest for a lectureship with a visitor giving three seminars. My colleagues and I debated over whom to ask to deliver the first such set of Gassman lectures, and Peter emerged as a superb choice. I was privileged to be asked to invite him and serve as host.

I found my 1994 letter to him (the wonders of hard drives...), which said: "Paul’s death was a tragic loss to our department and to chemistry itself. In searching for someone to initiate the lectureship for which he left a bequest, we thought it appropriate to ask someone with the same deep insights into physical organic chemistry that characterized Paul’s own research. We could think of no one better suited than yourself." He expressed his appreciation to be asked with humility and dedication to the task, and he began his first lecture with a long and moving tribute to Paul. He took personal interest in everyone with whom he met that week -- students, staff, and faculty. His generosity of spirit at Minnesota was 100 percent consistent with what I had experienced as a graduate student at Illinois from 1983-1988. Peter had a dry wit, keen insights, and unstinting empathy. In the classroom, he had a depth of knowledge that never failed to inspire, and a passion to match.

My thoughts are with his family and his many students, postdocs, collaborators, colleagues, all of whom must feel the loss still more keenly than I, blessed though I was with even my peripheral acquaintance. Our positive influence on others is our most lasting legacy, and Peter's will be enduring.

Gideon expressed to everyone in the Department of Chemistry his great regret regarding the passing of Prof. Beak. "Peter was a close friend and colleague in science for many years."

“In 1968, with our only interaction being a brief potential project outline, Peter accepted me for undergraduate research. Other undergrad friends had highly recommended him to me. My senior year in his laboratory convinced me that I wanted to be a chemist (rather than attend med school). He suggested four or five graduate schools and described potential advisors at each one. Peter’s insight into these advisors and me was remarkable! After receiving my doctoral degree with one, I had a post doc with another, and later became collaborators/friends with two others. Although I only heard him lecture once, he was clearly a talented and committed teacher. Peter’s research addressed chemistry questions with a depth and thoroughness which provided a complete understanding of the problem. Later in my own career, I often thought about how I saw him working with graduate students individually or as a group to prepare them for their next step in their careers. It is a behavior to emulate. Peter exhibited exceptional caring warmth which is rare in academic environments. He gave thoughtful, encouraging advice, usually making me think differently about the situation. Peter was my academic father.”

Dr. Beak was my advisor while I attended the UIUC chemistry program from 1984 to 1988. Every time I saw him for counsel, I remember him always being fully engaged with the young man sitting in front of him. His kindness and enthusiasm always left me feeling that he truly cared about his students. The program was tough. He encouraged me to persevere and tried to help me navigate school and life. His example made me realize that you can be a scientist and be human. I have enjoyed a great career in chemistry and science. Who knows where I would be if I didn't have those experiences with Professor Beak. Thank you, Dr. Beak!

“Peter’s recent passing leaves a hole in my heart. I worked on directed metalation chemistry as a graduate student in the Beak group from 1978-1982. This training, along with my postdoc, prepared me well for 35+ successful years as a medicinal chemist at Abbott, then AbbVie, working in viral and other infectious diseases. I am exceedingly grateful for the opportunities I had to study with Peter, to be mentored by him, and to interact with him as a colleague.

Peter was kind and supportive as a mentor, and an excellent teacher. He uniquely combined a humble and gentle personality with an insistence on scientific integrity, mechanistic rigor and critical thinking. This role modeling prepared me well for assuming scientific leadership later in my career. As I advanced through my graduate program, Peter’s visits to my lab for an update became deliberately less frequent, as he encouraged me to develop my own ideas and work more independently. As the end neared, he was instrumental in helping me to secure a postdoctoral position. Later, it was a pleasure to continue to learn from Peter over the years at Abbott where he served as a consultant. If you had a vexing chemistry problem, you could always rely on Peter following up with suggestions and literature references.

In more recent years, it has been wonderful for my wife and I to occasionally visit with Peter and Sandy as close friends. I observed Peter supporting his colleagues, particularly young faculty members, with the same generosity of spirit that he supported us as students. He never lost his love of chemistry, his passion for teaching, or his desire to help others become better people. I am sure that I am not alone in feeling today that the chemistry community has lost one of its heroes, for I have lost one of mine.”

I was one of the earliest PhDs to come out of the Beak laboratory, right at the beginning of his amazing, long, and unique career, receiving my degree in summer of 1968. I think I was about number five or six. Jim Bonham, Ron Trancik, Virgil Weiss, and John Meisel all had preceded me, but I lost track of others that may have finished up before them. None of the very exciting breakthrough stuff with lithium reagents, etc., had yet taken place in the Beak group, so reading today about all of this in the many posted accolades on the Illinois Department of Chemistry web page was just so fascinating. I agree with every observation regarding the character and contributions of this man — Professor Beak surely will be recalled by careful chemical historians as a giant, just like Roger Adams or Nelson J. Leonard or Reynold Fuson.

I was perhaps the only black sheep emerging from the Beak group because I did not spend the rest of my life thinking about organic chemistry. After a brief sojourn in industry here in Minnesota, I borrowed a lot of money at near-Mafia rates, entered medical school at the University of Minnesota at age 29, and then ultimately became a surgeon after residency and was invited to stay on as a faculty member there for my career. It must be said that my University of Illinois education, and most especially the exposure to Peter Beak, had in retrospect profound positive influences on my life as an academic surgeon (now retired). This may sound odd to non-surgeons, but it is definitely true. Just two examples: I learned from Professor Beak the value of Persistence when working on any tough problem — he is supposed to have opined that “Persistence is always more important than intelligence"; and I learned from him also the vital importance of Constant Attention to Detail, not only in actions taken but most especially in the ways we think about problems. Take my word for it, those are both extremely important in the world of both "doing surgery” and teaching surgery to young trainees, regardless of the specialty involved.

Peter Beak was the most-humble person I have ever known. He was world-famous but utterly unpretentious. That combination in a professor is darned rare in any academic department anywhere. He was also a “triple threat” teacher in this sense: his humility made him approachable; his genius was obvious, and he could almost read your mind; and he knew an old trick of pedagogy that I learned from one of my surgical teachers many years after my Urbana days. That trick is illustrated by the following wisecrack: “We know all the answers already around here -- what we REALLY need are some good questions”. Peter Beak was always, and I mean always, able to pose questions that broke through to a grad student’s mental machinery and suggested new trails to follow. He was a pure scholar and Socrates would have just nodded his head “yes.” Beak was an expert in what I like to call “responsible analogical reasoning," something that seems easy to do but always has numerous pitfalls when attempted by amateurs.

He was a remarkably great man, and my only regret today is that I did not stay in closer touch with him or the chemistry department over the years. We did very occasionally communicate however, and my closing vignette illustrates something that several other Beak group graduates alluded to in their posts: He could not stand idly by whenever there was even a whiff of pretense or some display of self-promotion by somebody. Although I was many years post-Urbana when it happened, I got my one full dose of the polite “Beak Correction” as follows: In mid-career at Minnesota as a faculty man I had become involved in a modest amount of expert witness work, both in malpractice and in product liability legal cases. For that reason, I ordered some special bond stationery that had on its top line in large font my name and the degrees MD and PhD afterwards. This stationery was used for sending invoices, answering queries from lawyers, etc. In much smaller font directly below my name I had listed on three lines these three credentials: Fellow, American College of Surgeons; Fellow, Infectious Diseases Society of America; and Fellow, Society for Hospital Epidemiology of America. I had sent Peter a letter using that stationery, I think in response to a personal medical question he had asked me. In response, I got a phone call from Urbana rather quickly — and it was brief. He said words to the effect, “that sure is a fancy letterhead you are using. . . . .get rid of it.” Point taken and the whole supply was shredded the very next day.

In sum, a very old aphorism comes to mind now and it is my recollection that it is chiseled in stone over the gate outside some ancient monastery somewhere in rural Asia: “When the student is ready a teacher will appear.” The first time I read this, about twenty years ago, I immediately reflected on my days at Illinois. All 100 of us who were lucky enough to somehow be ready when we joined the Beak group over the years were richly rewarded in often concealed ways that have never faded.

“The most I admire about Professor Beak is his devotion to the teaching and research of chemistry.

I was his graduate student for four years from 1983-1987. As a graduate student, I was in the classroom during the day and lab doing research at night. I recall that every evening and weekend I worked in the lab, he was always in his office, without fail. There were many occasions during my graduate study where his teaching, guidance, mentoring and support was invaluable. One such occasion was when I had to present my research at an annual ACS meeting for being awarded the Organic Fuson Award. At that time, I had only been in the U.S. for three years with very limited verbal communication skills and no presentation experience. Professor Beak worked with me slide by slide to make sure I had a successful presentation. I also remember the red marks from him on every page of my thesis from his diligent proofreading.

His contribution to chemistry speaks for itself in the many awards and recognitions that he received during his career. And yet he remained one of the humblest people I know.

After graduation, during the few occasions that we met, he always asked me ‘What can we do to further improve our graduate program?’, even after being moved to Emeritus status in 2008. His devotion to teaching never stopped. I, and others who were lucky enough to be mentored by Dr. Beak, will always remember the immense part he played in our success.

To establish the Professor Beak Graduate Travel Scholarship is to honor Professor Beak’s devotion to the Chemistry Education. It is also a way to help in improving the graduate program at the Department of Chemistry.”

My memories of Peter Beak all revolve around how comfortable he made me feel. I was not at all sure about what I wanted out of graduate school when I arrived at the U of I. It was only after my first visit with Peter that I finally felt that I had a clear direction and purpose. I know in my heart that one of the main reasons I obtained my degree was because of the way Peter put me at ease and made me feel welcome. Peter’s natural openness and genuine concern for the well-being of his students created an environment where I was able to reach my potential while actually enjoying the growing pangs along the way. Working with Peter gave me the foundation I needed to be comfortable to pursue different career options even when others thought my choices were unconventional. I recently finished my working chemistry career when I retired from teaching high school chemistry for the last 14 years. If my students felt some of what I felt when I worked with Peter, then I would consider that a successful career in and of itself.

Professor Beak played a significant role in my career, as he did with so many others. He provided me the freedom and the challenge to develop my thesis work into findings worthy of journal publication, while always being present to teach, support and guide when needed. Additionally, in my case, he provided the cogent argumentation not to pursue a law degree in concert with my pursuit of a PhD in chemistry, simultaneously at the U of I. It was a difficult decision for me, but I am very glad I accepted his advice and solely pursued the chemistry degree. It ultimately led to my becoming chairman of the board of the Industrial Research Institute, a global organization of technology leaders, based in Washington DC, and the first Chief Innovation Officer for the USG Corp.

He was also an exceptionally good athlete. We played several sports together, including basketball, tennis and racquetball during my tenure on campus. It was always fun and always competitive.

In summary, Professor Beak was a teacher and teammate initially and a colleague and a friend for life. He was truly an incredible man; an enlightened leader, who will always be remembered for his broad range of skills, kind demeanor and ready laugh. I am fortunate to have known him and worked for him.

From 1995-2000 I had the privilege and extreme fortune to be a student in Peter’s research group. It was only five years, but it was absolutely the most formative five years of my life. Peter shaped my mind, my work ethic, and my approach to interacting with colleagues. And in case that wasn’t enough, I also left his labs with a set of life-long, like-minded friends and my wife, Marna.

Like all his family, friends, former colleagues, and students, I’m deeply saddened that Peter is no longer physically in our lives. I do take solace, however, in knowing that his legacy will live on, and I enjoyed the process of making a top 5 list of things that I learned from Peter.

1) Conduct your business with professionalism. I never once saw Peter lose his cool or embarrass someone (Although to be completely fair if your proposed mechanism was described as “very creative” it wasn’t to be taken as a complement!). I did see him consistently strive towards the highest standards of rigor, fairness, and consistency.

2) To maximize your output, bring other experts to the table. For me this manifested itself in the encouragement I received to reach out to Dave Collum’s group for help with kinetics and Greg Girolami’s group for help with air-sensitive crystallization techniques. Peter himself was a close friend and co-author with Victor Snieckus, when the overlap of their research programs could have pushed them to competition.

3) It is possible to be both egoless and self-confident. Peter always deflected praise back to his students, but he also was self-confident enough to go head-to-head with other well-respected scientists. Even Peter’s walk carried a bit of determination and swagger. I’ll always smile thinking of a story from a fellow student that couldn’t keep up with a 60+ year-old Peter on a walk shared through the campus.

4) Make everyone feel important and mentor those coming behind you. Peter didn’t play favorites and I believe it was a big part of the harmony and collaborative spirit that existed in his group throughout my years. Everyone got to experience his inimitable laughter over a shared joke. Watching Peter help bring David Gin and Wilfred van der Donk through the early phase of their careers in joint group meetings is something that will always stick with me.

5) Don’t be afraid to lift the veil on your private life. Seeing Peter’s home for Christmas parties, learning about his childhood in New York, hearing about his children and their accomplishments, going out to dinner with Peter and Sandy on the occasion of my graduation… all of these things helped to make me see Peter as something more than a scientific mentor. He was a real, albeit extraordinary, human being. And that is a huge part of the fondness I will always have for him.

Marna and I thank everyone who has shared their memories. We join you in celebration for a life well-lived. There will never be another Peter Beak.

“Peter Beak had a profound impact on my life, and he is the reason I attended Graduate School at the University of Illinois. I first met Peter in January of 1971 on a campus visit, which he hosted. I was very impressed with the time he spent with me ‘selling the University of Illinois.’ In fact, Peter sold himself. I joined his group in September of 1972, only two weeks after the start of Fall Semester in August. I made this decision not because he was a brilliant chemist (which he was), but because I recognized that he was a brilliant chemist who cared about people, even first-year graduate students. Over the years, I became acutely aware that this decision would become one of the best decisions I would make in my entire life. I was very fortunate in that after graduation my student/mentor relationship with Peter would develop into a close personal and family relationship with both Peter and Sandy over the next 44 years. Two of my fondest memories are when they skied with my family and stayed at our condo in Lake Tahoe and when Peter, Sandy, my wife Beverly, and I celebrated his entry to the National Academy of Science with champagne in our dining room in St. Louis. I will truly miss Peter.”

“Dear Pete,

It’s been 52 years since we first met, but only a little more than a year since we last had dinner together. Sandy, you and me. I’ve been fortunate to have had the opportunity to return to Illinois Chemistry, seeing you several times over the past decade. You are the Mentor, who has had the single most impact on me, how I think, throughout my professional chemistry career and life. With some of your recognizable phrases, easy to recall, you taught me: “We’re smart, we can figure this out!”; “The big ones just fall harder.”; “For some, a PhD will be the highpoint of their career, others will keep going.”; and, of course, “If we’re wrong on this one, we’ll both be pushing a broom!”. Always, you would encourage me to use all of the tools known or build new, not just what’s convenient, familiar or available. In essence, very forward thinking, no problems are unsolvable. Pure inspiration, critical thinking and underlying hard work! Your intrinsic drive and penetrating insights will always be with me. Thank you, Peter for teaching me about inspiration, rigor, hard work and insights. You gave me the base I needed to keep going and build on.

Forever,

Brock Siegel (PhD, ’74, Beak)”

To submit a memory of Prof. Peter Beak for inclusion on this page, please e-mail Tracy Crane at tlcrane@illinois.edu.